3 Calibration Curves and Linear Regression in Excel

If you are currently participating in a timetabled BIOS103 QS workshop, please ensure that you cover all of this section’s content and complete this week’s formative and summative assessments in the BIOS103 Canvas Course.

In this section we’ll be re-visiting linear trendlines in Excel in the context of calibration curves and extending our knowledge by going deeper into the world of linear regression.

We will be working on two important skills:

- Manipulating data (transposing)

- Making predictions from linear models.

3.1 Calibration Curves

A calibration curve is a plot of a measurable quantity (in our case absorbance, as determined by spectrophotometry) against the concentration of known standards. This relationship, typically linear, allows for the determination of the concentration of unknown samples by interpolation.

The Beer-Lambert Law provides the foundation for generating calibration curves in spectrophotometry. It describes the relationship between absorbance (A) and the concentration (C) of a substance in solution. The law is given by the equation:

\[ A = m \cdot C \]

Where:

- A is the absorbance (a dimensionless quantity, i.e. no units!).

- m is the slope (related to molar absorptivity and path length).

- C is the protein concentration (in mg/mL).

There are a few key considerations to make when using this law to determine the concentrations of unknown solutions:

- Linear range: the calibration curve is only valid within a certain concentration range. At very high concentrations, the relationship may no longer be linear (due to factors like light scattering). Extrapolating concentrations from our calibration curves that are beyond those of our known standards is very, very naughty. Don’t do it!

- Reproducibility: It is critical that the same instrument (including scan settings and wavelength) be use for both the standards and unknowns.

Let’s take a look at an example dataset from an experiment designed to generate a calibration curve for hemoglobin. Assume that starting from a stock solution of concentration 1.5 mg/mL a set of seven protein solutions have been created using a 1:1 serial dilution and that the absorbance of each solution has been measured at a wavelength of 560nm (yellow-green light).

Mac Users

It might not be possible for you to transpose the data like in the video above. If you can’t, try this:

Select the range of data you want to rearrange, including any row or column labels, and Cmd+C to copy.

Select the first cell where you want to paste the data, and on the Home tab, click the arrow next to Paste, and then click Transpose.

Watch this video if you’re still stuck.

- Download the CSV File:

- Here is an example dataset. Download it to your local machine.

- Import into Excel:

- Open Excel (Use the desktop version - you won’t be able to do this using the online version!).

- Go to

Data > From Text/CSVand select the downloaded CSV file. - When the import wizard appears, do not click Load.

There’s something not right about this dataset. It’s sideways! The columns of data run horizontally instead of vertically. We don’t like this, it makes it much harder to plot figures and perform any analysis.

We need to transform the data somehow and flip it to vertical instead of horizontal. We need to transpose the data.

- Transpose the data:

- On the import wizard click the Transform Data button. This will open up a new window called Power Query Editor.

- Click the Transform tab and then click the Transpose button.

- Click the Use First Row as Headers button.

- Return to the Home tab and click Close & Load to import your transposed data.

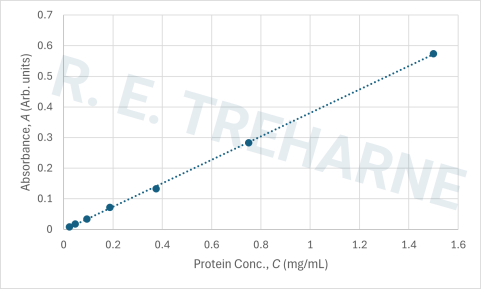

- Generate a Calibration Curve:

- Click anywhere on your data table.

- Click the Insert tab and select the Scatter chart from the charts option.

- Get rid of the title.

- Label the x-axis: “Protein Conc. (mg/mL)”.

- Label the y-axis: “Absorbance (Arb. units)”.

- Click the green plus (chart elements) icon at the top-right of the graph and select More options from Trendline.

- Add a linear trendline and check the box to “Display Equation on Chart”.

- If you’re including your figure in a report it’s better practice to include details of the \(m\) and \(b\) values that you extract in your figure caption like in figure 3.1.

- Use the Calibration Curve:

Now that you’ve extracted the m and b values from your calibration curve’s linear trendline you can use it to find the concentration of an unknown sample by measuring its absorbance.

Our calibration curve for the dataset gives us the equation:

\[ A = 0.3827 \cdot C - 0.0024 \]

If an unknown protein solution has an absorbance of 0.50, you can rearrange the equation to solve for concentration \(C\):

\[ 0.50 = 0.3827 \cdot C - 0.0024 \]

Solving for \(C\):

\[ C = \frac{0.50 + 0.0024}{0.3827} = 1.3 \, \text{mg/mL} \]

Thus, the concentration of the unknown protein solution is 1.3 mg/mL.

Note that I’ve expressed my answer to 2 significant figures to match the minimum level of precision available to me during the calculation (i.e. 2 s.f for both 0.5 and 0.0024).

Figure 3.1: Calibration curve for Hemoglobin determined from a standard set generated from a 1:1 serial dilution from a starting 1.5 mg/mL solution. Values of m=0.3827 and b=0.0024 were extracted from the linear relationship A = m * C + b, where b is the systematic error associated with the measurement (most likely related pipetting inaccuracies).

3.2 Linear Regression

A linear trendline is visually helpful, but what what Excel is actually doing behind the scenes is something more powerful: linear regression.

Linear regression is a statistical method used to quantify how much the variation in a dependent variable can be attributed to changes in an independent variable. It helps us understand how one variable predicts or influences another. Additionally, it provides insight into how much of the variation is due to error or other unaccounted factors, and whether we need to explore other relationships or variables that may better explain the observed patterns.

Linear regression models are valuable because they offer an estimation of the relationship between variables, and by extension, help in predicting future outcomes based on known values of independent variables.

Why “Linear”?

In nature, over relatively small ranges of dependent and independent variables, the relationship between them can often be approximated as linear. This means that as one variable increases or decreases, the other responds in a predictable and proportional manner. While not always the case, assuming linearity can be useful for many applications, especially for the scope of this course.

Independent and Dependent Variables:

- The independent variable is the one you manipulate or change to see its effect (e.g., hours of sunlight).

- The dependent variable is the one being measured or observed (e.g., sunflower growth).

These are sometimes referred to as explanatory and response variables, respectively.

Linear Regression as a Hypothesis Test

Performing a linear regression is also a test of a hypothesis. This time, our null hypothesis is that there is no linear relationship between the dependent and independent variables. In other words, any observed association between the two is just due to random chance.

More formally:

- Null Hypothesis (H₀): There is no linear relationship between the independent variable and the dependent variable. The slope of the regression line is equal to zero.

- H₀: β₁ = 0

(where β₁ represents the slope of the regression line)

- H₀: β₁ = 0

- Alternative Hypothesis (H₁): There is a linear relationship between the independent variable and the dependent variable. The slope of the regression line is not equal to zero.

- H₁: β₁ ≠ 0

3.2.1 The Linear Regression Equation

The linear regression equation provides a way to express the relationship between the independent variable (predictor) and the dependent variable (outcome) as a straight line:

\[ Y = β₀ + β₁X + ε \]

- Y: The dependent variable (outcome) we are trying to predict.

- X: The independent variable (predictor) we use to make predictions.

- β₀: The intercept, or the value of Y when X is 0. This represents the starting point of the relationship.

- β₁: The slope, or the change in Y for every one-unit increase in X. It tells us how steep the relationship is.

- ε: The error term, which accounts for the variance in Y that cannot be explained by X.

3.2.2 Performing a Linear Regression in Excel

Let’s work through an example using a full linear regression with Excel’s Analysis ToolPak. Suppose we’re investigating the growth per day of sunflowers (dependent variable) based on the number of hours of direct sunlight they receive each day (independent variable).

In this case, we want to determine if there is a linear relationship between hours of sunlight and sunflower growth. By performing the regression analysis, we’ll be able to assess if and how sunlight impacts sunflower growth, and how strong that relationship is.

Let’s get started with the analysis in Excel!

1. Download the data:

- Here is an example sunflower dataset. Download it to your local machine.

2. Import the data:

- Open up a new Excel workbook.

- Go to the Data tab and select the Import from csv/txt icon.

- Once the wizards has loaded click Load.

3. Perform Regression:

- Click anywhere on the sheet, select the Data tab again and select the Data Analysis button in the “Analysis” area of the tools ribbon.

- If you can’t see the button then you probably need to configure the Analysis ToolPak Add-In.

- Select “Regression” and click “OK”.

- Select the “Input Y Range” - This is your dependent variable, i.e. how much your sunflowers grew per day (column B). Include the header.

- Select the “Input X Range” - This is your independent variable, i.e. number of hours of direct sunlight per day (column A). Include the header.

- Tick the **Labels” box.

- Select the New Worksheet Ply output option

- Check all the remaining boxes for Residuals and Normal Probability sections.

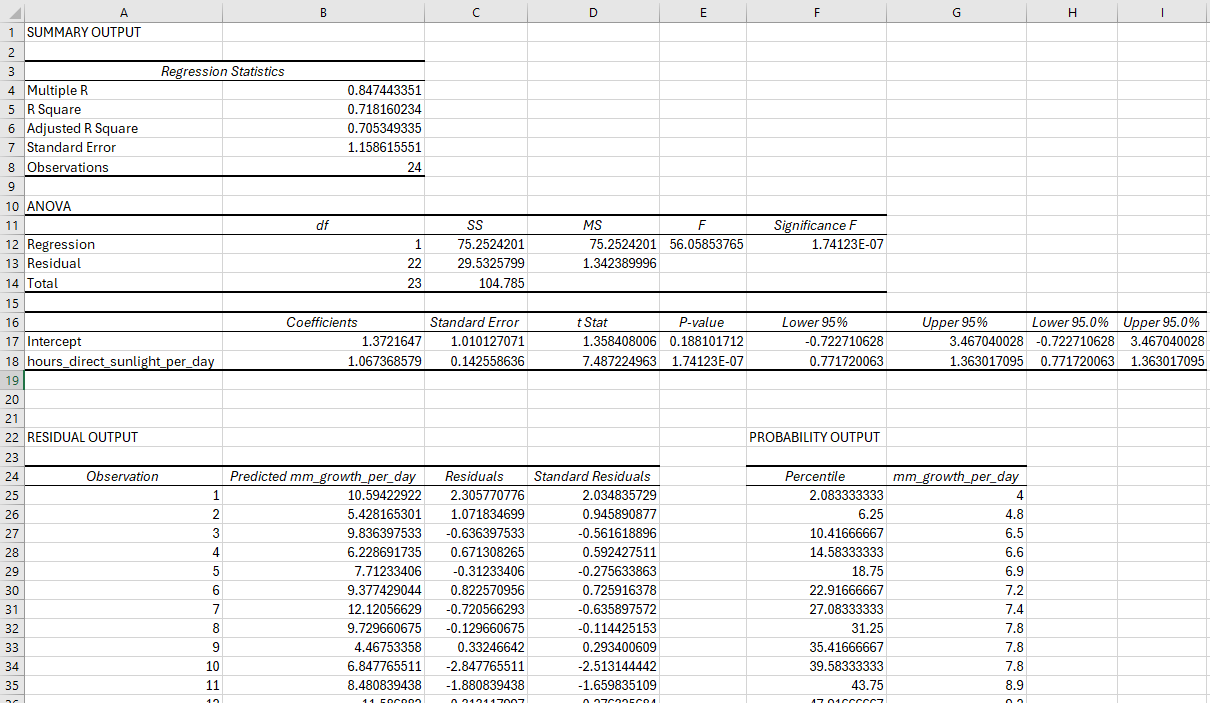

- Click OK. Hopefully, you’ll see something like that shown in figure 3.2.

Figure 3.2: This is what you should see after performing a regression on your example sunflower dataset using Excel’s Analysis ToolPak Add-In.

3.2.3 Interpreting Your Linear Regression

Wow! Your linear regression has provided so much information—it can feel like an avalanche at first. But don’t worry, not all of it is important for our purposes. Let’s focus on what is interesting and useful.

1. Summary Output Table:

Multiple R: This is the correlation coefficient between your observed and predicted values. It ranges from -1 to 1. A value closer to 1 or -1 indicates a strong relationship, whereas a value close to 0 means a weak relationship. In our case, a value of 0.65 indicates a reasonably strong correlation between growth and sunlight.

R Square (R²): This tells us how much of the variance in the dependent variable is explained by the independent variable(s). In our case, an R² of 0.42 means that 42% of the variation in the dependent variable is explained by the model. Conversely, it means that approx 58%, i.e. the majority, of the variance is explained by other unknown variables. In this context, these unknown variables could include things like daily average temperature, rainfall, humidity etc.

Adjusted R Square: This adjusts the R² value for the number of predictors in your model. It’s more useful when dealing with multiple independent variables as it accounts for any unnecessary complexity added by too many variables.

Standard Error: This measures the average distance that the observed values fall from the regression line. A smaller standard error means a better fit. Note that the units of your standard error are the same as for your dependent variable, i.e. mm.

2. ANOVA Table

The ANOVA table tells us whether the overall regression model is significant.

Degrees of Freedom (df): This refers to the number of independent pieces of information that went into calculating the estimates. It’s a balance between the number of observations and the number of predictors in the model.

SS Regression (Sum of Squares due to Regression): This represents the variance in the dependent variable explained by the model.

SS Residual (Sum of Squares of Residuals): This represents the variance that the model doesn’t explain.

Significance F: This is the p-value for the overall regression model. In our case, A p-value < 0.05 means that the model is statistically significant, and we reject the null hypothesis that there is no relationship between the dependent and independent variables.

3. Coefficient Table

This table is where you’ll find the key parameters for your linear regression model.

Intercept (β₀): This is the expected value of the dependent variable when the independent variable is zero. In other words, it’s your y-intercept value.

Gradient (β₁): This is the slope of your line, showing how much the dependent variable changes with each unit increase in the independent variable.

P-values: These tell us whether the coefficients (intercept and gradient) are statistically significant. If the p-value for the gradient is less than 0.05, we can say that the independent variable has a significant impact on the dependent variable.

4. Residual Plots and Additional Tables

Residual Plot: This plot shows the differences between the observed and predicted values (residuals). Ideally, these residuals should be randomly scattered around 0, indicating a good model fit. If this is not the case then it might not be appropriate for you to be performing a linear regression.

Normal Probability Plot: This checks if the residuals follow a normal distribution. If the points follow a straight line, the residuals are normally distributed. Again, if this is not the case then you should seek an alternative analysis.

Residual Output: This provides detailed information about each residual (the error for each observation).

Probability Output: Provides the probabilities of observing these residuals given the model fit.

3.2.4 Making Predictions with Our Model

With the insights from our linear regression analysis, we can now use our model to make predictions using the equation

\[ \hat{Y} = \beta_0 + \beta_1 \hat{X} \]

where: - \(\hat{Y}\) is the predicted value of the dependent variable. - \(\beta_0\) is the intercept, representing the expected value of \(Y\) when \(X\) is zero. - \(\beta_1\) is the gradient (or slope), indicating how much \(Y\) changes with a one-unit change in \(X\). - \(\hat{X}\) is the value of the independent variable for which we want to make a prediction.

For example, to predict the daily growth of our sunflowers when they’ve received six hours of sunlight:

\[ \hat{Y} = 2.449 + ( 0.898 \times 6 )= 7.836 \]

So, the predicted value of \(\hat{Y}\) for \(\hat{X} = 6\) is \(7.836\) \(mm\).

But wait! Couldn’t I have achieved this by simply adding a trend line to a plot of \(X\) vs. \(Y\), as discussed in section @ref{section:calibration-curves}? Yes, you could have extracted the coefficients \(\beta_0\) and \(\beta_1\) from the equation of the line, and even added the \(R^2\) value to the plot. So why go through all this additional work?

The full regression analysis allows us to determine the standard error (\(SE\)) of the model, which enables us to calculate the uncertainty associated with a predicted value \(\hat{Y}\). This is something we couldn’t do with a simple trend line!

This uncertainty, often referred to as the margin of error (\(ME\)), provides the range within which future individual observations are expected to fall.

To calculate \(ME\):

\[ ME = t \times SE \]

where \(t\) is the t-statistic which, in this context, can be drawn from a Student’s t-distribution and accounts for the uncertainty in estimating the population parameters from a sample. In excel you can calculate \(t\) using:

=T.INV.2T(alpha, df)- alpha is the significance level, in this case 0.05.

- df is the degrees of freedom which can be calculated as \(df = n - k - 1\) where \(n\) is the number of data points (observables) and \(k\) is the number of independent variables. In our case, \(n=24\) and \(k=1\) so \(df=24-1-1=22\).

3.2.5 Extending to Multiple Variables

Right now, we’re focusing on simple linear regression (one dependent and one independent variable). However, what if we wanted to examine the effect of multiple independent variables (e.g., sunlight and temperature on sunflower growth)? This is called multiple regression and we’d consider the following linear regression equation instead:

\[ Y = \beta_0 + \beta_1 X_1 + \beta_2 X_2 + \dots + \beta_n X_n + \epsilon \]

Where:

- \(X_1, X_2, ..., X_n\): The independent variables (e.g., sunlight, temperature, etc.).

- \(\beta_0\): As before, this is the intercept, representing the expected value of \(Y\) when all independent variables are 0.

- \(\beta_1, \beta_2, ..., \beta_n\): The coefficients of the independent variables, representing the change in \(Y\) for a one-unit change in \(X\), assuming all other variables remain constant.

Multiple regression allows us to assess the combined effect of several factors, which is crucial when studying complex systems where multiple variables might influence the outcome.

Unfortunately, Excel has its limits for this. But don’t worry—we’ll tackle multiple regression using R later!

3.3 Complete your Weekly Assignments

In the BIOS103 Canvas course you will find this week’s formative and summative QS assignments. You should aim to complete both of these before the end of the online workshop that corresponds to this section’s content. The assignments are identical in all but the following details:

- You can attempt the formative assignment as many times as you like. It will not contribute to your overall score for this course. You will receive immediate feedback after submitting formative assignments. Make sure you practice this assignment until you’re confident that you can get the correct answer on your own.

- You can attempt the summative assignment only once. It will be identical to the formative assignment but will use different values and datasets. This assignment will contribute to your overall score for this course. Failure to complete a summative test before the stated deadline will result in a zero score. You will not receive immediate feedback after submitting summative assignments. Typically, your scores will be posted within 7 days.

In ALL cases, when you click the button to “begin” a test you will have two hours to complete and submit the questions. If the test times out it will automatically submit.