2 Summarising Data and ANOVA in Excel

If you are currently participating in a timetabled BIOS103 QS workshop, please ensure that you cover all of this section’s content and complete this week’s formative and summative assessments in the BIOS103 Canvas Course.

In this section we will only be using Excel. No R today! Specifically, you will be developing two important skills:

- Summarising Data.

- Constructing and testing hypotheses.

The ultimate aim is to gain insight and learn something new about the world from the data that we have painstaking measured in our well designed lab experiments. This is a cornerstone of what being a scientist is all about.

2.1 Summarising Data

Raw data is beautiful, but messy. Showing another person your raw data and expecting them to immediately understand it, no matter how proud you are of the toil expended to generate the data, is an unrealistic expectation. You need to boil your data down into something that another person can grasp instantaneously.

Let’s take a look at a Zebrafish dataset from an experiment that is uncannily similar to the one you performed in your lab practical this week.

2.1.1 Download and Import the CSV File

- Download the CSV File:

- Here is an example dataset. Download it to your local machine.

- Import into Excel:

- Open Excel (Use the desktop version - you won’t be able to do this using the online version!).

- Go to Data > From Text/CSV and select the downloaded CSV file.

- When the import wizard appears, click Load.

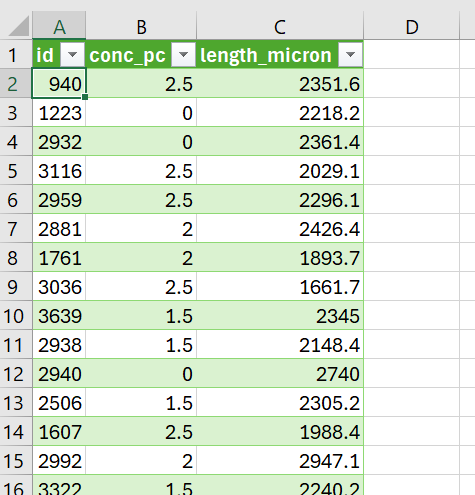

You should now see something like that in Figure 2.1. There are 3 columns:

- ID - A unique number to identify a measurement.

- conc_pc - The ethanol concentration (%) that the each embryo was treated with.

- length_micron - The measured lengths, in \(\mu m\) of the embryos.

We call this format, in which each row corresponds to a single measurement, a long format.

Figure 2.1: You should see this (or something like it) after you have imported your date into Excel.

2.1.2 Generating a Summary Table

Excel Alternative

If you are having trouble accessing the Desktop version of Excel then here is an alternative video. “Summary Table with Google Sheets”

- Identify your Groups

- Click anywhere in your table.

- Select the Data menu and click the Advanced icon in the Sort & Filter section. This will bring up a window called “Advanced Filter”.

- Select the Copy to another location action.

- Your list range should already be set to $B:$B, but if not make it so.

- Set the Copy to cell to E1

- Make sure the Unique records only check box is selected and click OK.

- You should now see a complete list of your alcohol concentration groups in a column with a header conc_pc. Make this into a new table by clicking on any of the concentration values, and then Insert > New table > OK.

Nice. Now you’re ready to start building out your summary table horizontally. Let’s start with calculating the mean Zebrafish length for each group.

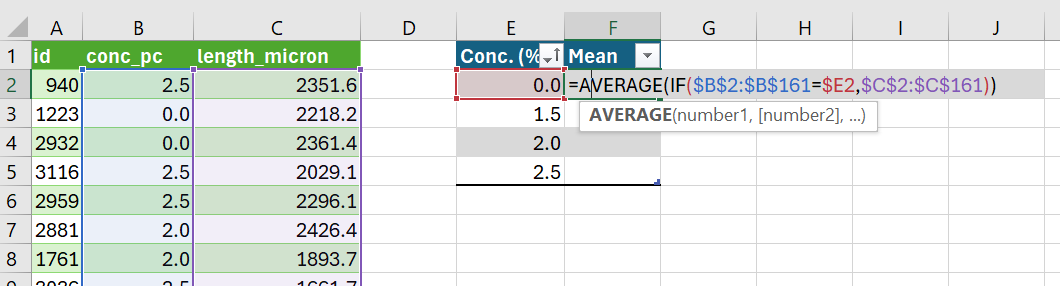

Right now, your spreadsheet should look roughly the same as the screenshot in figure 2.2

Figure 2.2: Constructing a summary table

- Calculating a Mean Column

- Create a new column in your summary table by typing the word Mean in cell F1.

- Calculate the mean of the Zebrafish lengths for the control group (0% alcohol concentration) by entering the following formula into cell F2.

=AVERAGE(IF($B1:$B$161=$E2,$C1:$C$161))

A Deeper Explanation

The formula

=AVERAGE(IF($B$2:$B$161=$E2,$C$2:$C$161))is an array formula that calculates the average length of Zebrafish for a specific group based on the concentration of alcohol. It’s a bit of a beast isn’t it? Let’s break it down.

$B$2:$B$161: The $ symbols before both the column letter B and the row numbers 2 and 161 lock the entire range. This means that when you copy the formula to other cells, this range will not change; it will always refer to cells B2 to B161.

$E2: The $ before the column letter E locks the column, but since there’s no $ before the row number 2, the row number can change if the formula is dragged down across rows. This cell is used to compare each value in the range $B$2:$B$161 to the specific concentration value in the corresponding row in column E.

$C$2:$C$161: Similar to the range for column B, this locks the range of cells in column C from which the values will be averaged, conditional on the IF statement.

AVERAGE(IF(…)): The IF function checks each row in the range $B$2:$B$161 to see if it matches the value in the corresponding row in column E. If it matches, the corresponding value in column $C$2:$C$161 is included in the average calculation. The AVERAGE function then calculates the mean of these filtered values.

This approach is particularly useful when you want to calculate conditional averages across a dataset, ensuring that the correct cells are referenced even when copying the formula to different parts of the spreadsheet.

- Calculating More Columns

- Create four more columns with headers:

- Std. Dev.

- Median

- Min

- Max

- Drag the cell F2 to G2. Change the word AVERAGE in the formula in G2 to STDEV. This will calculate the standard deviation for the group and the remaining cells in the column should also auto complete.

- Do the same for the median, min and max columns. Be sure to use the corresponding function.

- Create four more columns with headers:

A Deeper Explanation

When analysing data, it’s important to understand the basic statistical measures that summarise the data’s distribution. Here are some key terms:

Mean: The mean, often referred to as the average, is the sum of all values in a dataset divided by the number of values. It provides a central value for the data. However, the mean can be influenced by outliers (extremely high or low values).

Standard Deviation: The standard deviation measures the amount of variation or dispersion in a dataset. It is calculated as the square root of the variance, where variance is the average of the squared differences between each data point and the mean. A low standard deviation indicates that the data points tend to be close to the mean, while a high standard deviation indicates more spread out data.

Median: The median is the middle value in a dataset when the values are arranged in ascending or descending order. If the dataset has an odd number of values, the median is the central value. If the dataset has an even number of values, the median is the average of the two central values. The median is less affected by outliers compared to the mean.

Min: The minimum (min) value is the smallest value in the dataset. It provides a measure of the lower bound of the data.

Max: The maximum (max) value is the largest value in the dataset. It provides a measure of the upper bound of the data.

These measures are fundamental for understanding the distribution of data. The mean and median give you central tendencies, while the standard deviation tells you how spread out the data is. The minimum and maximum values provide the range within which all the data points fall.

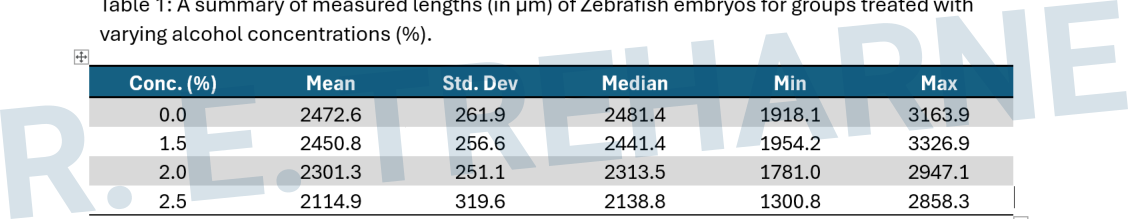

2.1.3 Presenting Your Summary Table

At some point you may wish to include your Excel summary table in a Word document. There’s a lot of wiggle room on how you choose to format your table but there are a few unbreakable rules:

- The table MUST have a caption.

- The caption should be placed ABOVE the table (not below as for a figure or graph).

- The caption should be numbered accordingly. For example, if this is the first table in your document the figure caption should start “Figure 1: …”.

- The caption should be descriptive and unambiguous. The reader should be able to quickly interpret what is going on without having to read the body of the text. Any symbols or variables or units should be defined in the caption.

- The data should be formatted to a sensible number of decimal places (i.e. if you’re measurements are made to 1 decimal place, your summary values should not be quoted to more than this).

Follow these rules and you can’t go wrong. Figure 2.3 shows how my summary table looks when copied and pasted into Word. I like to make my tables span the entire width of my document using the Auto-fit to window command. I also like to center my columns. These are personal preferences, but you can’t deny they look great!

Figure 2.3: Formatting a summary table in Microsoft Word.

2.2 Analysis of Variance (ANOVA)

You’re about to learn a critical skill that is important for becoming a scientist: formulating hypotheses and testing them. This is a cornerstone of scientific inquiry.

You’ve already summarised your data using descriptive statistics. Now, we’ll move on to another branch of statistics called inferential statistics. This involves using an appropriate statistical test to determine whether specific hypotheses that we construct should be accepted or rejected.

Knowing which statistical test to use depends on the data and context. It takes time and lots of practice to become proficient at this, and it’s completely normal to forget which test you need or how to interpret the result.

We’ll stick with out Zebrafish dataset and perform an Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) to determine whether there is something we can learn from our data. We’ll formulate a hypothesis and use Excel to perform the ANOVA. Then we’ll interpret the results.

But before we dive into this, let’s create a boxplot to visually inspect the data and see if we can generate some gut intuition as to what might be going on.

2.2.1 Grouped Boxplots in Excel

You might not have seen a grouped boxplot before. That’s OK. I’m confident that you’ll have a good intuition for what they show. However, for more information the key components of a boxplot read the text in the Anatomy of a Boxplot section. Let’s dive straight in for now though.

Create the Boxplot

Excel Alternative

If you are having trouble accessing the Desktop version of Excel then here is an alternative video. “Boxplots with Excel Online”

- Insert a Boxplot:

- Select your data.

- Go to the Insert tab, click on Insert Statistical Chart, and choose Box and Whisker.

- Select Data:

- Your plot will look a bit weird. That’s because we need to configure the groupings properly.

- Click the Select data button.

- Remove the conc_pc series from the left-hand list.

- Click the Edit button on the (currently empty) right-hand list.

- Boxplots in the wrong order?

- Sort the conc_pc column from smallest to largest.

- Re-scale y-axis:

- It’s best to re-scale the y-axis to maximise the space used by the boxplots. This will make any effect easier to see.

- Double-click on the numbers in the y-axis. Set the Bounds > Minimum: to 1000.

- Add Axis Labels:

- Click the green + icon in the top-right of your graph.

- Check the Axes titles box.

- Double-click on each label in turn and update with appropriate labels:

- X-axis: “Alcohol Conc. (%)”

- Y-axis: “Embryo Length (\(\mu m\))

- Note: To use the \(\mu\) symbol click Insert > Symbols > Symbol. Find the symbol in the list and click Insert.

- Get Rid of Chart Title:

- If you’re going to be presenting this figure in a report or poster then it should not have a title above the axes.

- Instead you should include a figure caption below the plot.

- The same unbreakable rules for your caption are the same as those described above for table captions. Just make sure your caption is below the figure instead of above.

- Export Your Figure:

- Right click on your figure anywhere outside the plot area and you should see the option to Save as picture.

- Save it somewhere sensible as a .png file and then insert it into a Word document with a sensible caption.

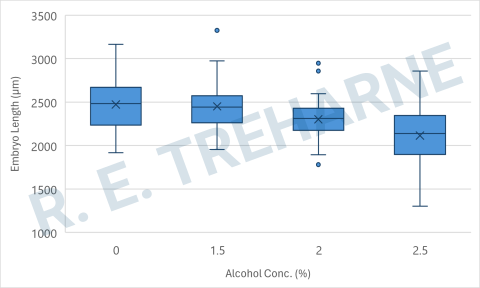

Figure 2.4: Distribution of Zebrafish embryo lengths organised by Alcohol treatments.

Interpret the Boxplot

Figure 2.4 shows our finished boxplot.

- Alcohol Concentration 0%:

- The median embryo length is approximately 2500 µm, with the mean slightly above the median.

- The data is relatively spread out, as shown by the wide box and long whiskers.

- There are no outliers in this group.

- Alcohol Concentration 1.5%:

- The median length is slightly lower than the 0% group, but the mean is still fairly close.

- The box and whiskers are narrower than in the 0% group, indicating less variability in embryo length.

- One outlier is present above the whisker, indicating a particularly large embryo in this concentration or possibly, a random measurement error.

- Alcohol Concentration 2%:

- The median and mean have both decreased, showing a reduction in embryo length as alcohol concentration increases.

- The box is narrower, indicating less variability, but there are several outliers both above and below the whiskers, suggesting that while most embryos were of a similar size, a few were much larger or smaller.

- Alcohol Concentration 2.5%:

- The median and mean lengths have further decreased, indicating a continued negative effect of alcohol concentration on embryo length.

- The box is of similar size to the 2% group, but with longer whiskers, indicating more variability in the data.

- There is one outlier below the whisker, indicating a particularly small embryo in this concentration.

In summary, As alcohol concentration increases, the median and mean embryo lengths decrease, indicating a negative correlation between alcohol concentration and embryo length. Variability in embryo length decreases slightly up to 2% concentration but then increases again at 2.5%, as evidenced by the longer whiskers. The presence of outliers, particularly at higher concentrations, suggests that while most embryos are affected similarly, some experience more extreme changes in size.

However, visual patterns alone cannot confirm the existence of a true relationship between alcohol concentration and embryo length. To rigorously explore whether the observed trends are statistically significant or merely due to chance, we must construct testable hypotheses. This process will allow us to formalise our observations and set the stage for appropriate statistical analysis.

Anatomy of a Boxplot

A boxplot is a standardised way of displaying the distribution of data based on a five-number summary: minimum, first quartile (Q1), median, third quartile (Q3), and maximum. The box in the boxplot represents the interquartile range (IQR), which is the range between Q1 and Q3. The central line within the box indicates the median, which is the middle value of the dataset.

Sometimes, an “X” symbol is also included within the box, representing the mean of the dataset. However, it is important to note that the mean is not always shown in a boxplot.

The “whiskers” of the boxplot extend from the box to the smallest and largest values within 1.5 times the IQR from the first and third quartiles, respectively. These whiskers help to indicate the spread of the majority of the data.

Outliers are data points that fall outside the range defined by the whiskers. These are typically plotted as individual points beyond the ends of the whiskers, highlighting data points that are unusually high or low compared to the rest of the dataset.

To determine whether a data point is an outlier, you compare it to the thresholds defined by the IQR:

- Any data point below Q1 - 1.5 * IQR is considered a lower outlier.

- Any data point above Q3 + 1.5 * IQR is considered an upper outlier.

Summary:

- Box: Represents the interquartile range (IQR), the middle 50% of the data.

- Central Line: Indicates the median value.

- X (if shown): Indicates the mean value.

- Whiskers: Extend to the smallest and largest values within 1.5 times the IQR from the quartiles.

- Outliers: Data points that lie outside the whiskers, typically displayed as individual points.

2.2.2 Constructing Testable Hypotheses

Given the patterns observed in the boxplot, where higher alcohol concentrations appear to be associated with shorter embryo lengths, it is essential to move from visual interpretation to a more rigorous statistical approach. This involves constructing and testing hypotheses to determine whether the observed trends are statistically significant.

Formulating the Hypotheses

In the context of your data, the primary goal is to determine whether different alcohol concentrations have a statistically significant effect on embryo length. To do this, we formulate a null hypothesis (\(H_{0}\)) and an alternative hypothesis (\(H_{1}\)):

Null Hypothesis (\(H_{0}\)): There is no statistically significant difference in the mean embryo lengths between the different alcohol concentration groups. Any observed differences are attributed to random variation rather than an effect of alcohol concentration.

\[ H_0: \bar{x}_0 = \bar{x}_{1.5} = \bar{x}_2 = \bar{x}_{2.5} \]

Here, \(\bar{x}_0\), \(\bar{x}_{1.5}\), \(\bar{x}_2\), and \(\bar{x}_{2.5}\) represent the mean embryo lengths at 0%, 1.5%, 2%, and 2.5% alcohol concentrations, respectively.

Alternative Hypothesis (\(H_{1}\)): At least one of the mean embryo lengths differs significantly from the others, suggesting that alcohol concentration has a measurable impact on embryo length.

\[ H_1: \text{At least one } \bar{x} \text{ is different} \]

The Origin of Hypothesis Testing

Hypothesis testing emerged in the early 20th century through the work of statisticians like Ronald A. Fisher, who applied these methods to agricultural experiments, leading to significant advancements in statistical methodology. However, Fisher’s legacy is also marred by his support for eugenics, reflecting the darker intersections of early statistical science with discriminatory ideologies.

While hypothesis testing remains central to scientific research, the use of p-values has faced criticism. P-values, often misinterpreted, simply measure data compatibility with the null hypothesis, not the truth of the hypothesis itself. The conventional threshold (p < 0.05) can lead to arbitrary decisions, and practices like p-hacking undermine the validity of results.

Alternatives and complements to p-values include confidence intervals (which offer a range of likely values for parameters), Bayesian methods (which incorporate prior knowledge into probability assessments), and effect sizes (which quantify the magnitude of an effect).

Understanding these tools and their limitations enables researchers to draw more nuanced and reliable conclusions from their data.

Getting Ready to Test

A One-way ANOVA is a statistical test used to determine whether there are significant differences between the means of three or more independent (unrelated) groups. In this case, the groups are the different levels of alcohol concentration (0%, 1.5%, 2%, and 2.5%).

The term “one-way” refers to the fact that we are analysing the effect of a single factor (alcohol concentration) on the dependent variable (embryo length). If we were interested in analysing the impact of an additional dependent variables (e.g. incubation temperature), as well as any interaction effects with alcohol concentration, we would likely want to perform a “two-way” ANOVA.

We are using ANOVA in this context because:

Multiple Group Comparisons: We have more than two groups (four alcohol concentration levels), and ANOVA is designed to handle comparisons across multiple groups simultaneously. This is more efficient and statistically sound than performing multiple t-tests, which would increase the likelihood of Type I errors (false positives).

Assessing Variability: ANOVA compares the variability within each group (i.e., how much embryo lengths vary within each alcohol concentration) to the variability between groups (i.e., how much the group means differ from each other). This helps us determine if the observed differences in means are greater than what we would expect by chance alone.

Assumptions of ANOVA

For ANOVA to be valid, certain assumptions must be met:

- Independence of Observations: The data points in each group are independent of each other. In other words, each data point corresponds to a unique embryo.

- Normality: The distribution of the residuals (differences between observed and predicted values) should be approximately normal.

- Homogeneity of Variances: The variances within each group should be roughly equal.

In this case, I have engineered the dataset so that these assumptions are met. However, in practice, when working with real data, it is crucial to check whether these assumptions hold before applying ANOVA. If the assumptions are violated, the results of the ANOVA may not be reliable, and alternative methods may be necessary. I’ll show you how to check that the assumptions for a statistical test are met in Chapter 5 and the available alternative tests for cases where the assumptions are not met.

2.2.3 Performing a One-Way Anova in Excel

Excel Alternative

If you are having trouble accessing the Desktop version of Excel then here is an alternative video. “ANOVA with Google Sheets”

Please be reminded that the guidance in the video above, and in the text below, is only relevant if you are using the desktop version of Excel on a Windows machine. It might work on a Mac - there’s no guarantee, and it won’t be relevant if you are using Google Sheets. If you can’t do the following with your personal device then please use one of the University machines.

Step 1: Install and Activate the Data Analysis ToolPak

To perform a One-Way ANOVA in Excel, you need to install and activate the Analysis ToolPak add-on.

- Open Excel and go to File > Options.

- In the Options menu, select Add-ins.

- At the bottom, next to “Manage”, ensure Excel Add-ins is selected and click Go.

- In the Add-Ins box, check the Analysis ToolPak option and click OK.

- You should now see a Data Analysis button in the Data ribbon.

Step 2: Create a Pivot Table to Reshape Data

Before performing the ANOVA, you need to reshape your long data into a wide format using a pivot table. Here’s how to do it:

- Select your dataset (including headers).

- Go to the Insert tab and click on PivotTable.

- In the Create PivotTable dialog box, select where you want the PivotTable to be placed (e.g., New Worksheet).

- In the PivotTable Fields pane:

- Drag conc_pc to the Columns area.

- Drag id to the Rows area.

- Drag length_micron to the Values area.

- The resulting pivot table will have the concentration levels as columns and the measurements as rows, which is the required format for One-Way ANOVA.

Step 3: Perform the One-Way ANOVA

- Click on the Data ribbon and select Data Analysis.

- In the Data Analysis dialog, select ANOVA: Single Factor and click OK.

- In the ANOVA: Single Factor dialog box:

- Input Range: Select the range of your reshaped data (including the labels).

- Grouped By: Choose Columns (since each group is in a separate column).

- Labels in First Row: Check this option if you included labels.

- Alpha: Set this to 0.05 (the default significance level).

- Output Options: Choose where you want to display the results (e.g., New Worksheet Ply). You can name the new sheet “Results”.

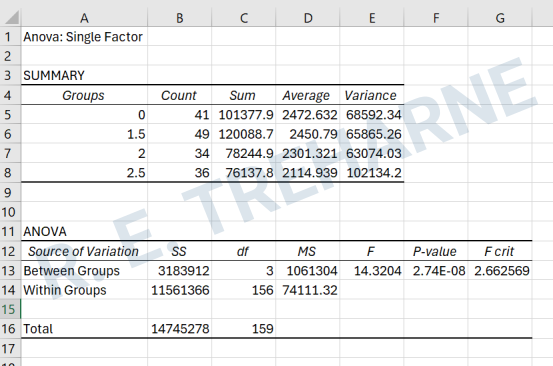

- Click OK to run the analysis. You should see a new sheet that looks identical to that shown in 2.5.

Figure 2.5: Results tables of one-way ANOVA in Excel

Step 4: Interpret the Results

Excel will generate a new worksheet with the ANOVA results. The output includes two tables:

- Summary Table:

- Count: Number of observations in each group.

- Sum: Sum of all values in each group.

- Average: Mean value of each group.

- Variance: Variability within each group.

- ANOVA Table:

- Source of Variation:

- Between Groups: Variability between the groups.

- Within Groups: Variability within each group.

- SS (Sum of Squares): Measure of the total variation.

- df (Degrees of Freedom): Calculated as the number of groups minus 1 for between groups, and total observations minus the number of groups for within groups.

- MS (Mean Square): SS divided by df.

- F (F-Statistic): Ratio of MS between groups to MS within groups.

- P-Value: Indicates if the results are statistically significant.

- F crit: Critical value of F for the given alpha level.

- Source of Variation:

Step 5: Make a Conclusion

- Compare the P-Value to the alpha level (0.05):

- If P-Value ≤ 0.05, reject the null hypothesis and conclude that there is a significant difference between the groups.

- If P-Value > 0.05, fail to reject the null hypothesis and conclude that there is no significant difference between the groups.

In your ANOVA result, a p-value of 2.48E-08 means that the probability of observing the differences between your group means by random chance is exceedingly low (just 0.0000000248). Since this p-value is far below the common threshold of 0.05, we can reject the null hypothesis (\(H_0\)), and conclude that there are statistically significant differences between the groups.

While the one-way ANOVA tells us that there are significant differences between the groups, it does not specify which groups differ from each other. To determine where these differences lie, additional testing, known as post-hoc testing, is required. Post-hoc tests, allow us to compare the group means directly and identify which specific groups are significantly different. Although post-hoc testing requires a bit more work, it can significantly enhance our understanding of the data and provide deeper insights into the relationships between groups.

Understanding Exponent Notation

In statistical analysis, particularly when working with software like Excel or R, you might values expressed in scientific notation, often using the letter “E” followed by a number. For example, the p-value 2.48E-08 appears in your ANOVA results.

What Does 2.48E-08 Mean?

The notation 2.48E-08 is Excel’s way of representing the number 2.48 × 10⁻⁸. Here’s how to break it down:

- 2.48: This is the base number.

- E-08: This indicates that the base number (2.48) should be multiplied by 10 raised to the power of -8.

So, 2.48E-08 is mathematically equivalent to:

\[ 2.48 \times 10^{-8} = 0.0000000248 \]

This value is extremely small, which is typical for p-values when the test results are highly significant.

Why Use Scientific Notation?

Scientific notation is used to conveniently express very large or very small numbers that would otherwise be cumbersome to write out in full. In the case of p-values, this format is particularly useful because significant results often involve very small numbers. Instead of writing 0.0000000248, which can be error-prone and hard to read, Excel uses 2.48E-08 to convey the same information succinctly.

2.2.4 Performing Post-hoc Tests in Excel

Following a significant ANOVA, we need to perform additional tests to determine where the differences between the groups lie. These are called Post-hoc tests.

Step 1: Create a new table to list group comparisons

- In cell A19, underneath your ANOVA result table, Create a new column label called Groups.

- List all the possible ways two groups can be compared to each other (there are six ways in total):

- 0% v 1.5%

- 0% v 2.0%

- 0% v 2.5%

- 1.5% v 2.0%

- 1.5% v 2.5%

- 2.0% v 2.5%

- Create additional column headers P-value and Significant? in cells B19 and C19 respectively.

Step 2: Perform T-tests for each group comparison

- Starting in cell B20 type:

=TTEST(wide!B$4:B$164, wide!C$4:C$164, 2, 2)- Copy the cell down for the remaining rows and update the columns in the formula to correspond with the respective groups that are being compared.

What is a T-test?

Unlike ANOVA, which compares multiple groups simultaneously to see if there are any significant differences in the means of the groups, a T-test can only compare two groups at a time.

The assumptions for a T-test are similar to those for ANOVA: the data should be normally distributed, the samples should be independent, and the variances of the two groups should be equal if using a two-sample T-test assuming equal variances.

Like ANOVA, the key output of a T-test is the p-value.

In Excel you perform a T-test like this:

=T.TEST(list1, list2, tails, type)where:

- list1: Corresponds to the list of values in your first group.

- list2: Corresponds to the list of values in your second group.

- tails: Requires a value of 1 or 2 indicating whether the test is one-tailed or two-tailed respectively.

- A one-tailed T-test tests for a difference in a specific direction (greater or less), while a two-tailed T-test tests for any difference regardless of direction.

- type: Requires a value of 1, 2, or 3 indicating:

- 1: A paired t-test (i.e., groups are not independent).

- 2: An independent t-test with equal variances between groups.

- 3: An independent t-test with unequal variances between groups (also known as a Welch test).

T-tests are powerful for pairwise comparisons but need to be used in conjunction with corrections like Bonferroni when multiple T-tests are conducted, as performing multiple tests increases the risk of Type I errors (false positives).

Let’s create a new table underneath my ANOVA table in Excel, say starting in cell A19

Step 3: Calculate Bonferroni Corrected Alpha Level - To calculate the Bonferroni corrected alpha level divide the initial threshold value of 0.05 by the number of t-tests you are performing, i.e. 6. - Use the corrected value by comparing it to the p-value of each of the t-tests to determine if the difference in the means of groups is significant.

Step 4: Extend Your Conclusions

The post-hoc tests indicate that there are significant differences in embryo lengths were found between the following pairs of alcohol concentrations:

- 0% vs. 2%

- 0% vs. 2.5%

- 1.5% vs. 2%

- 1.5% vs. 2.5%

These findings suggest that increases in alcohol concentration from 0% to 2%, and from 1.5% to 2.5%, lead to significant changes in embryo length.

Feedback Please.

I really value your feedback on these materials for quantitative skills. Please rate them below and then leave some feedback. It’s completely anonymous and will help me improve things if necessary. Say what you like, I have a thick skin - but feel free to leave positive comments as well as negative ones. Thank you.

2.3 Complete your Weekly Assignments

In the BIOS103 Canvas course you will find this week’s formative and summative QS assignments. You should aim to complete both of these before the end of the online workshop that corresponds to this section’s content. The assignments are identical in all but the following details:

- You can attempt the formative assignment as many times as you like. It will not contribute to your overall score for this course. You will receive immediate feedback after submitting formative assignments. Make sure you practice this assignment until you’re confident that you can get the correct answer on your own.

- You can attempt the summative assignment only once. It will be identical to the formative assignment but will use different values and datasets. This assignment will contribute to your overall score for this course. Failure to complete a summative test before the stated deadline will result in a zero score. You will not receive immediate feedback after submitting summative assignments. Typically, your scores will be posted within 7 days.

In ALL cases, when you click the button to “begin” a test you will have two hours to complete and submit the questions. If the test times out it will automatically submit.