6 Statistics in R: Part I

If you are currently participating in a timetabled BIOS103 QS workshop, please ensure that you cover all of this section’s content and complete this week’s formative and summative assessments in the BIOS103 Canvas Course.

The aim of this chapter is to show that there are often several ways to approach data analysis. Here, we’ll use R to perform tasks we’ve previously done in Excel. Why make the switch? While Excel is widely used (and is still extremely useful), R can greatly reduce the need for manual data transformations that Excel often requires, making data handling much easier and more efficient. Also, creating R scripts provides a clear, reproducible record of your analysis which is incredibly important for anyone who wishes to repeat your analysis and confirm your results.

Key learning objectives for this chapter include:

- Reading data direct from the web using R.

- Organising and cleaning your data in R ready for analysis.

- Performing a One-Way ANOVA and post-hoc tests in R.

- Performing a Two-Way ANOVA and post-hoc tests in R.

- Visualising relationships between two independent variables and a dependent one.

6.1 One-Way ANOVA in R

This section is almost a complete re-run of section 2.2. Except what we did in Excel, we’ll learn to do in R. I strongly recommend that you have a quick scroll through the whole of section 2.2 right now to refresh your memory. Seriously, do it.

6.1.1 Importing Data from an Online Source

Before we begin, did you know that the humble read.csv() function can also read a CSV file from a URL, making it extremely easy to work with datasets stored online.

The code below imports a CSV file containing zebrafish data, which includes information about the length of zebrafish embryos under various concentrations of alcohol. The read.csv() function fetches the data from the provided URL, which points to a raw GitHub file.

Create a new R project for this week and start a new script file. Copy the following lines the the file and run them.

# Read data direct from the web!

zebrafish_data <- read.csv("https://raw.githubusercontent.com/rtreharne/qs/refs/heads/main/data/02/zebrafish_999.csv")

# Convert the conc_pc column into a factor. IMPORTANT!

zebrafish_data$conc_pc <- as.factor(zebrafish_data$conc_pc)

# Inspect the data

head(zebrafish_data)## id conc_pc length_micron

## 1 2146 0 2103.4

## 2 3853 0 2703.3

## 3 2313 2 2279.5

## 4 1638 2.5 2020.8

## 5 1669 2.5 1708.4

## 6 2644 2.5 2256.3After importing the data, we convert the conc_pc column (which represents alcohol concentration percentages) into a factor variable using as.factor(). This is important because factors are categorical variables in R, and we’ll treat them as such in our analysis. Note that if you don’t perform this step then you’ll get errors when trying to do ANOVA.

Finally, the head() function is used to display the first few rows of the data, giving us an overview of its structure. This is a common way to check that the data has been loaded correctly and to understand the initial format of the dataset.

By importing data directly from an online source, you can quickly access and analyse datasets without needing to manually download and load files, streamlining your workflow. You’re welcome.

6.1.2 Summarising (Descriptive Statistics)

The code below will calculate descriptive statistics for the zebrafish dataset to summarise the length of the zebrafish embryos (length_micron) across different alcohol concentrations (conc_pc). Remember, descriptive statistics provide a quick overview of the central tendency and variability within the data, helping us understand patterns and outliers.

# This code extends the code block above.

# Calculate summary statistics for each group

zebrafish_summary <- aggregate(length_micron ~ conc_pc, zebrafish_data, function(x)

c(Mean = mean(x), Median = median(x), Max = max(x), Min = min(x), SD = sd(x)))

# Convert the list to data frame

zebrafish_summary <- do.call(data.frame, zebrafish_summary)

# Inspect the summary

print(zebrafish_summary)## conc_pc length_micron.Mean length_micron.Median length_micron.Max

## 1 0 2410.874 2451.15 2890.1

## 2 1.5 2405.318 2397.05 2975.6

## 3 2 2300.736 2279.50 2666.3

## 4 2.5 2105.539 2157.30 2692.1

## length_micron.Min length_micron.SD

## 1 1859.5 251.2151

## 2 1962.4 255.3249

## 3 1746.3 206.8577

## 4 1548.2 266.6929We begin by using the aggregate() function, which allows us to group the data by alcohol concentration (conc_pc) and calculate several statistics for each group: the mean, median, maximum, minimum, and standard deviation (SD). These metrics help us understand the typical value (mean and median) and the spread (max, min, SD) within each concentration level.

Once the summary statistics have been calculated, we convert the output from the aggregate() function (which is in list form) into a more manageable data frame format using the do.call(data.frame, ...) function. This makes it easier to inspect and manipulate the results.

To examine the summary statistics, we print() the zebrafish_summary dataframe. This provides an organised view of the key statistics for each group in the dataset.

Finally, it is a good practice to save your results to a file. In this case, we save the zebrafish_summary dataframe to a CSV file, allowing us to easily store, share, or reload the data for further analysis. The write.csv() function does this, ensuring the summary statistics are saved in a structured format, without row names, for easy use in future work. As before, you can import this .csv into Excel to style it for a report.

6.1.3 Grouped Boxplots in R

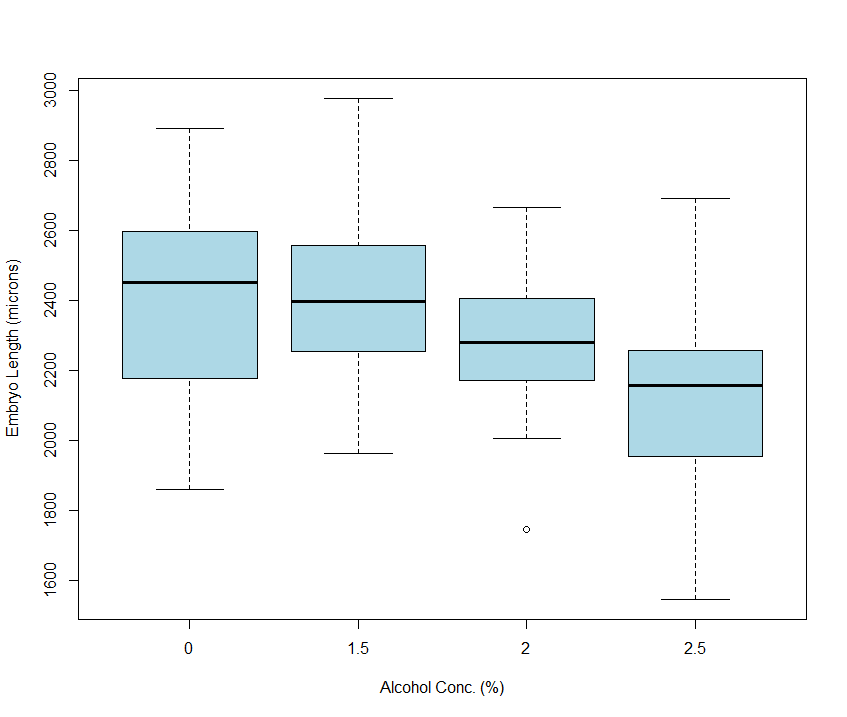

As before, the best way to visualise our dataset is using a grouped boxplot. Can you remember how fiddly this was in Excel? We had to create a pivot table before we could make a plot - yuck. Not so in R! The code below let’s us get the job done quickly, without faffing to produce the plot shown in figure 6.1.

# This code extends the code blocks above.

# Generate a grouped boxplot

boxplot(

length_micron ~ conc_pc, data = zebrafish_data,

main = "",

xlab = "Alcohol Conc. (%)",

ylab = "Embryo Length (microns)",

col = "lightblue"

)

Figure 6.1: Distribution of Zebrafish embryo lengths organised by Alcohol treaments.

My interpretation of the plot is exactly the same as that discussed in section 2.2.1.

6.1.4 Conducting a One-Way ANOVA

We are about to perform a One-Way Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) in R to examine whether there is a statistically significant difference in zebrafish embryo lengths across different alcohol concentrations. ANOVA allows us to compare the means of more than two groups to determine if any of the group means are different from each other.

The code below does the job in a single line. Beat that Excel!

# This code extends the code blocks above.

# Perform a One-Way ANOVA.

zebrafish_aov <- aov(length_micron ~ conc_pc, data = zebrafish_data)

# See the key results.

summary(zebrafish_aov)## Df Sum Sq Mean Sq F value Pr(>F)

## conc_pc 3 2485048 828349 13.64 5.97e-08 ***

## Residuals 156 9470556 60709

## ---

## Signif. codes: 0 '***' 0.001 '**' 0.01 '*' 0.05 '.' 0.1 ' ' 1We use the aov() function in R, where length_micron is the dependent variable (embryo length) and conc_pc is the independent variable (alcohol concentration). The function generates an ANOVA table that summarises the results of the test.

The output from the summary() function shows the following key components:

Df (Degrees of Freedom): This indicates how many independent pieces of information are used to estimate the variance. For conc_pc, the degrees of freedom is 3, as there are four levels of alcohol concentration. The residual degrees of freedom (156) corresponds to the leftover variation after accounting for the groups.

Sum Sq (Sum of Squares): This value represents the total variability in the data. The conc_pc group has a sum of squares of 2,485,048, indicating a considerable amount of variation between the different alcohol concentrations.

Mean Sq (Mean Square): The mean square is the sum of squares divided by the corresponding degrees of freedom. This gives us an estimate of the variance within each group. The mean square for conc_pc is 828,349.

F value: Sometimes referred to as the “F Statistic”, this is the ratio of the mean square of the group (between-group variation) to the mean square of the residuals (within-group variation). A large F value suggests that the group means are likely different. In this case, the F value is 13.64, which is quite large.

Pr(>F) (p-value): This is the probability of observing an F value as extreme as the one calculated, under the null hypothesis that all group means are equal. A small p-value indicates strong evidence against the null hypothesis. In our case, the p-value is 5.97e-08, which is very small (much smaller than 0.05), suggesting that there is a statistically significant difference between the groups.

The significance codes at the bottom of the output indicate the level of significance: here, *** means a highly significant result.

Interpretation: Since the p-value is extremely small (much less than 0.05), we reject the null hypothesis that all group means are equal. This means there is a statistically significant difference in embryo lengths across the different alcohol concentrations. This result suggests that the alcohol concentration has a notable effect on the growth of the zebrafish embryos.

In the next step, we will conduct post-hoc tests to further investigate which specific groups differ from each other.

6.1.5 Post-Hoc Tests

As discussed previously in section 2.2.4, after running an ANOVA, a significant result tells us that there is at least one difference among the group means, but it doesn’t specify which pairs of groups differ. To identify the specific group pairs with significant differences, we use post-hoc tests. In this section, we apply Tukey’s Honest Significant Difference (HSD) test to perform pairwise comparisons and determine which group means differ significantly.

In R, we can do this be extending our previuos code with two simple lines:

# This code extends the code blocks above.

# Perform TukeyHSD

tukey_result <- TukeyHSD(zebrafish_aov)

# View the results

print(tukey_result)## Tukey multiple comparisons of means

## 95% family-wise confidence level

##

## Fit: aov(formula = length_micron ~ conc_pc, data = zebrafish_data)

##

## $conc_pc

## diff lwr upr p adj

## 1.5-0 -5.555388 -148.8123 137.70156 0.9996328

## 2-0 -110.137912 -252.4274 32.15154 0.1886631

## 2.5-0 -305.334785 -445.8132 -164.85636 0.0000005

## 2-1.5 -104.582524 -250.4332 41.26814 0.2487027

## 2.5-1.5 -299.779397 -443.8638 -155.69500 0.0000014

## 2.5-2 -195.196873 -338.3194 -52.07438 0.0029202Interpreting the Output

- Comparisons: Each row corresponds to a comparison between two groups (e.g., 2.5-0).

- Mean Difference: The diff column displays the difference in means between groups. Confidence Interval: The lwr and upr columns give the 95% confidence interval for each difference.

- Adjusted p-value: The p adj column provides the p-values adjusted for multiple comparisons (like for our Bonferonni correction).

In the output, pairs with small p-values (e.g., 2.5-0 with a p-value of 0.0000005) indicate significant differences in group means, confirming which specific pairs show statistically significant differences. In our case, there is a signficant difference between the conc_pc groups: 2.5-0, 2.5-1.5 and 2.5-2.

Who Was Tukey?

The

TukeyHSD()test is named after John Tukey, a key figure in 20th-century statistics known for his contributions to data analysis and multiple comparison techniques. Interestingly, while collaborating with Claude Shannon on information theory, Tukey coined the term “bit” (short for binary digit), leaving a remarkable legacy that spans statistics and computer science.

Tukey’s Honest Significant Difference (HSD) test is a post-hoc analysis specifically designed for use after an ANOVA. It helps to identify significant pairwise group differences while controlling for the family-wise error rate (the likelihood of at least one false positive across all comparisons).

Tukey’s HSD is widely favoured because it strikes a balance between controlling the family-wise error rate and maintaining sensitivity to detect real differences. By contrast, Bonferroni-corrected t-tests (what we used in Excel in section @ref{post-hoc-tests}) offer a more conservative approach, dividing the significance level by the number of comparisons, which can reduce the power of the test. While Bonferroni is useful in highly exploratory settings with numerous comparisons, Tukey’s HSD is particularly effective for balanced designs in ANOVA.

In summary, Tukey’s HSD test provides a clear, statistically sound approach to determine specific differences between groups, supporting a rigorous interpretation of ANOVA results.

6.2 Two-way ANOVA in R

In this section, we’ll explore how to perform a two-way ANOVA in R to evaluate the combined effects of two independent variables on a single outcome variable. For this example, imagine you are overseeing a series of experiments to understand how both pH level and temperature impact the activity of an enzyme. Data from ten independent groups has been consolidated to enable a comprehensive analysis.

It’s helpful to clarify the difference between one-way and two-way ANOVA. In a one-way ANOVA, we examine the effect of a single independent variable (or factor) on the dependent variable, allowing us to determine if there is a statistically significant difference in the outcome across different levels of that factor. However, a two-way ANOVA expands on this by allowing us to investigate two independent variables simultaneously. This approach not only assesses the effect of each factor independently (the “main effects”) but also explores the interaction effect — whether the influence of one factor on the outcome variable changes depending on the level of the other factor.

For instance, in our scenario, a two-way ANOVA allows us to answer questions like:

- Does pH level alone significantly affect enzyme activity?

- Does temperature alone have a significant impact?

- Most importantly, does the effect of pH on enzyme activity differ depending on the temperature?

Understanding these interactions is critical when both factors might influence the outcome in a combined or conditional manner, making two-way ANOVA a powerful tool for more complex experimental designs.

With this foundation, we can proceed to import and prepare the data for analysis.

6.2.1 Importing and Cleaning the Data

Start a new R script and copy/paste the code block below to read the example dataset to a variable called activity_data.

activity_data <- read.csv("https://raw.githubusercontent.com/rtreharne/qs/main/data/08/activity_999.csv")

head(activity_data)## group ph temperature activity

## 1 10 7 20 0.0448

## 2 5 7 20

## 3 9 9 40 0.0558

## 4 9 7 20 ERROR

## 5 4 9 20 -1

## 6 7 5 30 0.0423The dataset includes some key columns:

group: Identifier for each independent experimental group.ph: pH levels at which the enzyme activity was measured.temperature: Temperature at which the enzyme activity was measured.activity: The values in this column actually refer to the measured changes in absorbance of samples (using a spectrophotometer) over a period of time (typically minutes) - units: \(\Delta A/min\).

Since ph and temperature are categorical factors, we need to ensure they are correctly set as factors in R, otherwise our ANOVA won’t work. Let’s extend our code as follows:

# This code extends the code blocks above.

# Set ph and temperature as factors

activity_data$ph <- as.factor(activity_data$ph)

activity_data$temperature <- as.factor(activity_data$temperature)We also see that some rows have the value “ERROR” or -1. We need to “clean” our dataset to ensure that all rows with these values in the activity column are removed. We can do that by extending our script with the following:

# This code extends the code blocks above.

# Make activity column numeric.

activity_data$activity <- as.numeric(activity_data$activity)## Warning: NAs introduced by coercion# Remove any rows with NA values.

activity_data <- na.omit(activity_data)

# Insist that all values in activity column are positive. An example of subsetting with a conditional statement!

activity_data <- activity_data[activity_data$activity >= 0,]

# Re-inspect the data

head(activity_data)## group ph temperature activity

## 1 10 7 20 0.0448

## 3 9 9 40 0.0558

## 6 7 5 30 0.0423

## 9 3 7 40 0.0418

## 11 8 5 20 0.0441

## 12 7 9 20 0.0256Great! Now we should only have numerical data in our activity column. Before we learn how to perform a two-way ANOVA let’s try and visualise our data.

6.2.2 Visualising the data

Visualising data, before performing statistical tests, offers immediate insights into patterns, trends, and any anomalies that could impact analysis. It helps assess assumptions, identify outliers, and reveal interactions between variables, providing a foundation for selecting the right tests and ensuring accurate results. Although we know we’ll be performing a two-way ANOVA in this case, it’s often not always clear which test is best suited, or if assumptions have been met, until some preliminary visualisation has been carried out.

In this case, our good old friend the grouped boxplot might not be very helful. Boxplots are great at comparing distributions across levels of a single variable, but they’re limited when trying to visualise interactions between two factors. Instead, we can turn to a couple of alternatives that let us display the combined effect of tow factors on a dependent variable.

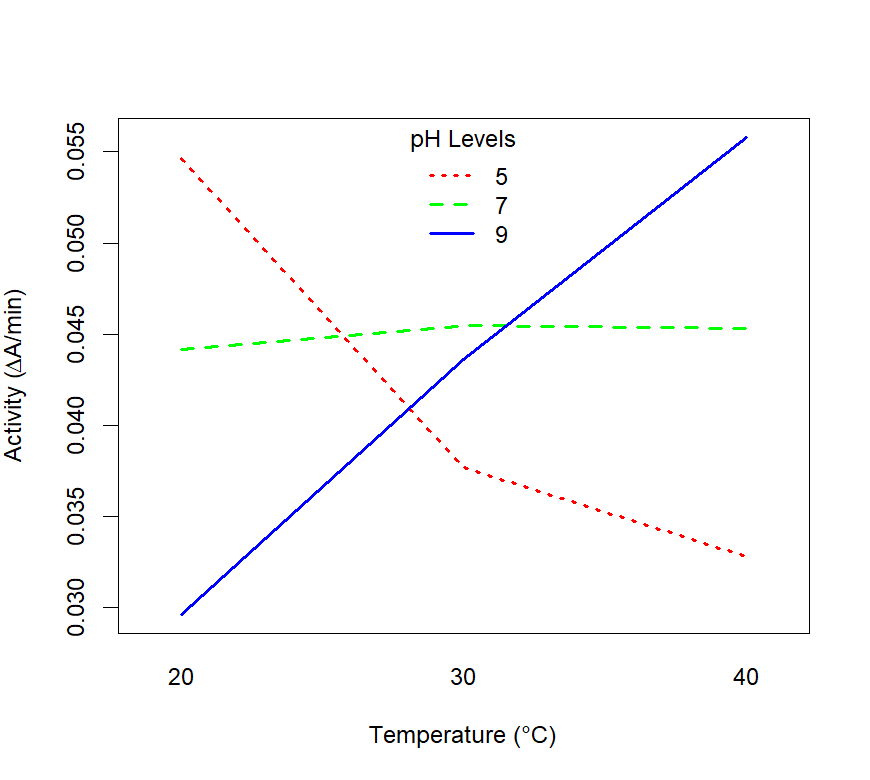

1. Interaction Plot

In an interaction plot, the levels of one variable are typically plotted on the x-axis, and the response variable is plotted on the y-axis. Different lines are drawn for each level of the second variable, and the lines’ slopes or patterns reveal if and how the variables interact.

Parallel lines suggest no interaction between the variables. Non-parallel lines indicate that the effect of one variable depends on the level of the other, showing an interaction.

Extend your script with the lines of code and run them to generate the plot shown in figure 6.2

# This code extends the code blocks above.

# Interaction plot of pH and Temperature on enzyme activity

interaction.plot(

activity_data$temperature, activity_data$ph, activity_data$activity,

col = c("red", "green", "blue"), lwd = 2,

xlab = "Temperature (°C)", ylab = expression("Activity ("*Delta*"A/min)"),

legend=FALSE

)

# Legend placement and formatting

legend(

"top",

legend = levels(activity_data$ph),

col = c("red", "green", "blue"),

lty = c(3, 2, 1),

lwd = 2,

title = "pH Levels",

bty= "n"

)Let’s break this code down so that we understand it comment by comment:

interaction.plot():- This function creates the main plot showing how enzyme activity changes with temperature and pH.

- Colours (

col = c("red", "green", "blue")) are used to distinguish between the different pH levels. - I’ve turned the default legend off using

legend = False, because it’s not as beautiful as I want it to be.

legend():- This function adds a custom legend at the top of the plot (

"top") where I think it looks best and doesn’t interfere with any of the plotted lines. - The legend items are based on the levels of the

phfactor. - The line types (

lty = c(3, 2, 1)) specify different styles (dotted, dashed and solid) to correspond tho the lines styles generated automatically byinteraction.plot(). - The

lwd = 2argument ensures the width of the lines in the legend match the line width used in the plot. - The

bty = "n"argument removes the box around the legend (this is optional, but I don’t like boxes around my legends because I’m fussy).

- This function adds a custom legend at the top of the plot (

Figure 6.2: Interaction plot showing the effect of temperature and pH on enzyme activity.

How should we iterpret what is going on in figure 6.2?

- pH = 5: The trend shows that the enzyme activity decreases as temperature increases and that activity is higher at 20 °C than for a pH of 7 and 9.

- pH = 9: The trend shows that the enzyme activity increases as temperature increases and that activity is higher at 40 °C than for a pH of 7 and 5.

- The lines for pH levels 5 and 9 cross each other, indicating an interaction between temperature and pH. I.e. the effect of temperature on enzyme activity changes depending on the pH level.

- pH = 7: there is little to no observable dependence of enzyme activity on temperature.

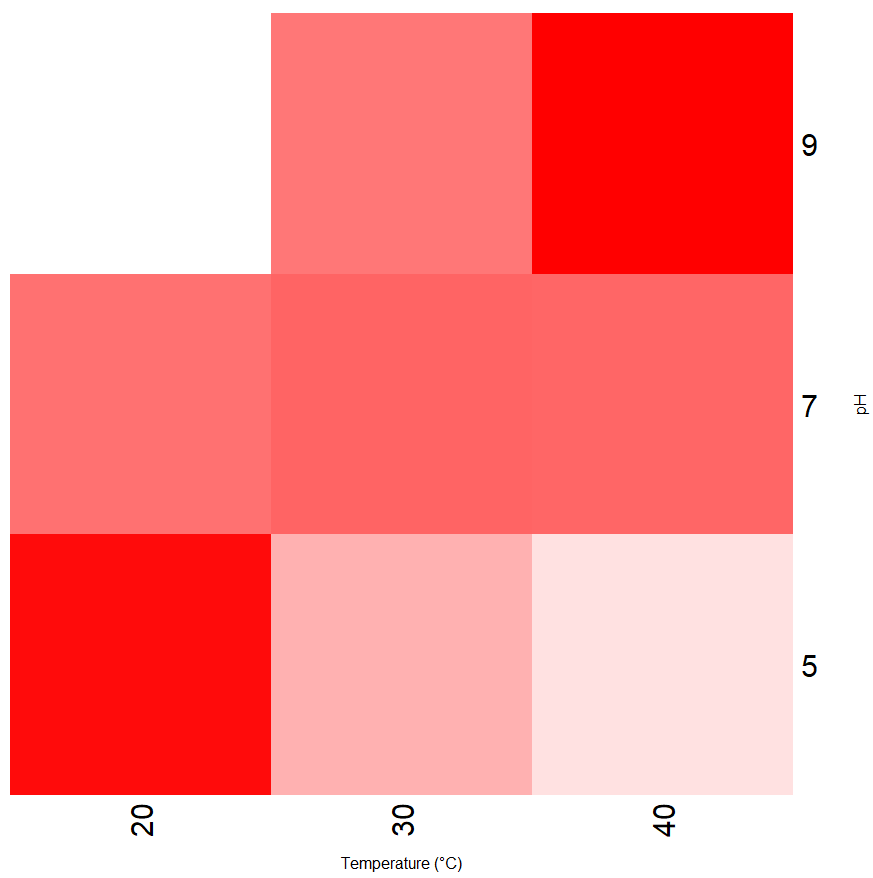

2. Heatmap

Another way of visualising the above is with a heat map. Try appending the following code to your script and running the lines to get the output shown in figure 6.3.

# This code extends the code blocks above.

# You'll need the reshape2 library for this one. You might need to install if first.

library(reshape2)

# Reshape the data for heatmap visualization

matrix <- acast(activity_data, ph ~ temperature, value.var = "activity", mean)

# Create a white-red color palette

color_palette <- colorRampPalette(c("white", "red"))(256)

# Create heatmap with blue-red colors and color key

heatmap(matrix, Rowv = NA, Colv = NA, scale = "none",

col = color_palette, # Use the blue-red color palette

xlab = "Temperature (°C)",

ylab = "pH",

margins = c(5, 5), # Adjust margins if needed

)

Figure 6.3: Heat map showing the interaction between temperature and pH on enzyme activity. Low activity is indicated by white and high activity by red.

If you can’t get this code to run then don’t worry, it’s not critically important (it won’t affect your ability to complete this week’s summative task). I just wanted to highlight that when it comes to visualisation in R, you’ve got lots of options. If you really want to understand what the code is doing then you can see what my good friend ChatGPT has to say about it.

I’d interpret the heatmap in figure 6.3 in exactly the same way as the interaction plot. One big disadvantage however, is that it only shows the relative changes in activity - I’d need to spend a bit of time figuring out how to put a colorbar key at the side of the plot to indicate activity values with respect to colour.

Right now though, I think we’d really better getting to the important bit though: Finally! A Two-way ANOVA.

6.2.3 Conducting a Two-Way ANOVA

Extend your existing script with the code below.

# This code extends the code block above.

# Perform a two-way ANOVA and save to a variable called "anova_result"

anova_result <- aov(activity ~ ph * temperature, data = activity_data)

# View a summary of the ANOVA

summary(anova_result)## Df Sum Sq Mean Sq F value Pr(>F)

## ph 2 0.000957 0.000479 25.05 1.21e-10 ***

## temperature 2 0.000490 0.000245 12.82 5.00e-06 ***

## ph:temperature 4 0.016283 0.004071 213.10 < 2e-16 ***

## Residuals 250 0.004776 0.000019

## ---

## Signif. codes: 0 '***' 0.001 '**' 0.01 '*' 0.05 '.' 0.1 ' ' 1And that’s it! You’ll notice that performing a two-way ANOVA in R is almost exactly the same as performing a one-way ANOVA. The critical difference is formula we use in the aov(): activity ~ ph * temperature. We’ve included both the factors (ph and temperatures) we’re interested in within the formula separated (confusingly perhaps!) with a * symbol.

The summary table is similar to what we would expect to see for a one-way ANOVA, but it’s got a few extra rows which we should discuss:

Main Effects (pH and Temperature):

- Each factor - pH and Temperature - has its own row in the table. the F values and p-values for each main effect tell us if that factor alone has a statistically significant impact on enzyme activity.

- In our case, both pH and Temperature have p-values well below the 0.05 threshold. This indicates that both pH and Temperature have a strong effect on enzyme activity.

Interaction effects (pH:Temperature):

- The interaction term, shown as ph:temperature, tells us if the effect of one factor depends on the level of the other factor.

- In our case, the interaction effect is highly significant (p < 0.001). this suggests that the impact of pH on enzyme activity changes depending on the temperature level, and vice versa.

6.2.4 Post-Hoc tests

We’re on the home stretch now. Now we’ve firmly established that there is some significant differences between the means of the groups we can proceed to perform our TukeyHSD():

## Tukey multiple comparisons of means

## 95% family-wise confidence level

##

## Fit: aov(formula = activity ~ ph * temperature, data = activity_data)

##

## $ph

## diff lwr upr p adj

## 7-5 0.0044183644 0.002823274 0.0060134552 0.0000000

## 9-5 0.0037190537 0.002168714 0.0052693932 0.0000001

## 9-7 -0.0006993107 -0.002264321 0.0008657001 0.5438710

##

## $temperature

## diff lwr upr p adj

## 30-20 -0.0002284719 -0.001817209 0.001360265 0.9386138

## 40-20 0.0027577790 0.001169042 0.004346516 0.0001698

## 40-30 0.0029862509 0.001450088 0.004522414 0.0000215

##

## $`ph:temperature`

## diff lwr upr p adj

## 7:20-5:20 -0.0104350631 -0.0141988811 -0.006671245 0.0000000

## 9:20-5:20 -0.0252768696 -0.0292283805 -0.021325359 0.0000000

## 5:30-5:20 -0.0169983696 -0.0207370550 -0.013259684 0.0000000

## 7:30-5:20 -0.0091688696 -0.0131203805 -0.005217359 0.0000000

## 9:30-5:20 -0.0110487484 -0.0147636697 -0.007333827 0.0000000

## 5:40-5:20 -0.0218908696 -0.0256813118 -0.018100427 0.0000000

## 7:40-5:20 -0.0093570234 -0.0132719529 -0.005442094 0.0000000

## 9:40-5:20 0.0011508951 -0.0025415202 0.004843310 0.9877802

## 9:20-7:20 -0.0148418065 -0.0185181802 -0.011165433 0.0000000

## 5:30-7:20 -0.0065633065 -0.0100099068 -0.003116706 0.0000003

## 7:30-7:20 0.0012661935 -0.0024101802 0.004942567 0.9769340

## 9:30-7:20 -0.0006136852 -0.0040344930 0.002807122 0.9997549

## 5:40-7:20 -0.0114558065 -0.0149584822 -0.007953131 0.0000000

## 7:40-7:20 0.0010780397 -0.0025589863 0.004715066 0.9912213

## 9:40-7:20 0.0115859583 0.0081896049 0.014982312 0.0000000

## 5:30-9:20 0.0082785000 0.0046278607 0.011929139 0.0000000

## 7:30-9:20 0.0161080000 0.0122396881 0.019976312 0.0000000

## 9:30-9:20 0.0142281212 0.0106018230 0.017854419 0.0000000

## 5:40-9:20 0.0033860000 -0.0003176267 0.007089627 0.1035482

## 7:40-9:20 0.0159198462 0.0120889101 0.019750782 0.0000000

## 9:40-9:20 0.0264277647 0.0228245260 0.030031003 0.0000000

## 7:30-5:30 0.0078295000 0.0041788607 0.011480139 0.0000000

## 9:30-5:30 0.0059496212 0.0025564856 0.009342757 0.0000036

## 5:40-5:30 -0.0048925000 -0.0083681555 -0.001416845 0.0005270

## 7:40-5:30 0.0076413462 0.0040303350 0.011252357 0.0000000

## 9:40-5:30 0.0181492647 0.0147807844 0.021517745 0.0000000

## 9:30-7:30 -0.0018798788 -0.0055061770 0.001746419 0.7918724

## 5:40-7:30 -0.0127220000 -0.0164256267 -0.009018373 0.0000000

## 7:40-7:30 -0.0001881538 -0.0040190899 0.003642782 1.0000000

## 9:40-7:30 0.0103197647 0.0067165260 0.013923003 0.0000000

## 5:40-9:30 -0.0108421212 -0.0142922013 -0.007392041 0.0000000

## 7:40-9:30 0.0016917249 -0.0018946761 0.005278126 0.8656961

## 9:40-9:30 0.0121996435 0.0088575587 0.015541728 0.0000000

## 7:40-5:40 0.0125338462 0.0088692746 0.016198418 0.0000000

## 9:40-5:40 0.0230417647 0.0196159301 0.026467599 0.0000000

## 9:40-7:40 0.0105079186 0.0069448352 0.014071002 0.0000000# You'll need these last two lines to complete your summative test this week

# Get the interaction effects table and conver to a dataframe

#tukey_df <- as.data.frame(tukey_result[["ph:temperature"]])

# Find the maximum absolute difference between the means of the ph:Temperature group-wise comparisons.

#max(abs(tukey_df$diff))Woah! That’s a lot of information. Let me try to summarise what’s going on here:

1. Main Effects: - pH: This part shows pairwise comparisons between pH levels: - 7-5: The difference in activity between pH 7 and 5 is significant (p adj < 0.05), with a positive difference of 0.0044. - 9-5: Significant difference, indicating pH 9 activity is lower than pH 5. - 9-7: Not significant (p adj = 0.484), indicating similar activity between pH 9 and 7. - Temperature: This section compares activity across temperature levels:

- 40-20 and 40-30 both show significant differences, suggesting that activity at 40°C is notably different from 20°C and 30°C.

- 30-20 is not significant, indicating similar activity between 20°C and 30°C.

2. Interaction Effects (pH:Temperature):

- Each combination of pH and temperature levels is compared. For instance:

- 7:20-5:20: Activity at pH 7 and 20°C differs significantly from pH 5 and 20°C.

- 9:40-7:40: A significant difference indicates pH 9 at 40°C differs from pH 7 at 40°C.

- Many combinations show significant differences (p adj < 0.05), especially involving pH 5 at 20°C. This likely reflects the complex interaction effects found in the ANOVA, showing how specific pH and temperature combinations impact activity differently.

General Tips for Interpretation:

- Significance: Look for adjusted p-values (p adj < 0.05) to identify significant differences.

- Positive or Negative Differences: The diff column tells you if one level has higher or lower activity relative to another.

- Interactions: Significant differences in the

interaction effectspH:Temperature` table suggest that the combined effect of pH and temperature is crucial for understanding enzyme activity.